[We've reached the end of 2012, and sadly a new OutKast album seems less likely to happen now than it did this time last year. Still, it would be wrong not to consider the year in André 3000, even if his output was limited to roughly one verse per fiscal quarter. NB that our ratings are based on the quality of 3000's verse(s) alone, not on the quality of the song or the contributions of other collaborators.]

Gorillaz, "DoYaThing" (Converse single)

AM: What begins as a routine Gorillaz song takes a turn when André arrives with his cartoony chorus and verse. That’s before he really goes off. By then, Murphy and Albarn have been transformed into André’s backing band, pumping out a retro-futuristic mix that sounds like the J.B.’s playing dissonant krautrock. André loses it, fuelling the frenzy by screaming “I’m the shit” in a dozen different permutations. Favorite one: “I’m the shit! Bear with me!” When the comedown arrives your head is still spinning. 4/5

NS: A collaboration between Andre 3000 and Damon Albarn already sounds cool on paper, but that still couldn't prepare anyone for the relentless dominance 3000 exerts over all 13 minutes of this high-BPM electropunk number (and you better believe the 13-minute head trip is the only way to listen). 3000's verses here arrive in three parts--the first, blisteringly fast free association, the second, punkish yelping, the third, scaled-back self-criticism. The effect is exhaustive, to say the least. 5/5

Frank Ocean, “Pink Matter” (Channel Orange)

AM: Even before Dré comes in, “Pink Matter” distinguishes itself as the prettiest song on Channel Orange (the shout-growls in the background work, somehow). But when the bass drops at 2:24, and especially when 3000 starts rhyming at 2:40, “Pink Matter” flies off to zones unknown. André plays a little guitar on the song, and sings, bringing things deep into Love Below territory. But it’s 3000’s verse that’s jaw-dropping--so fluid, so full of regret, rapped with such poise and wit, almost whispered, with sympathy and style, self-reflection and realness, gray matter and grace. Sixteen of the best bars I’ve heard, not just in 2012, not just from André, but ever. 5/5

NS: Channel Orange veers into 'Kastian territory (peep the bassline especially) at 2:24 of "Pink Matter," which is already a highlight in a record full of them. André's verse style here is reminiscent of the work he did with Drake last year, but "Pink Matter" has a less specific POV. Here, his work recalls Frank Sinatra on albums like In the Wee Small Hours, putting up a lonely, disengaged front to belie his disappointment with love and human interaction in general. Also, props to 3 Stacks for continuing to showcase his guitar lessons. Still, I'm confused by his withholding Big Boi from the record. Why the embargo on new OutKast collaborations, André? 4.5/5

Rick Ross, "Sixteen” (God Forgives, I Don't)

AM: The lush buildup sounds like it was lifted from Kaputt, and when 3000 wails the hook Ross and the J.U.S.T.I.C.E. League clinch their luxury rap pedigree. Whose brand is more coveted than the fashionable recluse from Kast? The whole conceit of the song is that sixteen bars constrain a rapper, so Ross gives Andre way, way more than that. 3000 delves into an extended reminiscence about being a kid, in a start-stop flow, leisurely making his way to the present. “Flipper didn’t hold his nose, so why should I hold my tongue?” he asks. After the megaverse, a double-tracked Dré gets freaky and Ross ad-libs, the latter giving little indication that he has any idea what André’s saying. When 3000’s extended guitar solo begins, you get the sense that the Bawse has lost control of his own song. 4/5

NS: Sometimes, sixteen bars is not enough to fully expound on complicated topics, such as one's life. This is the thesis of "Sixteen," and what's interesting about this song is how Rick Ross and André 3000 prove this in completely different ways. Rozay approaches his extended verse span as an opportunity to create a series of flashy, visual quick cuts, stylized filmmaking in the manner of the 70s masters he often references. Dré, on the other hand, is more concerned with wordplay, and the complexities and tangles of associations his varying rhythm choices generate in the listener's imagination. His verse is at turns personal, political, and purely syllabic, as he spins tales of childhood heartbreak and adult disappointment. And his guitar solo deserves more love than it got--I liken his scratchy, primitive style to David Bowie on Diamond Dogs. 5/5

T.I., “Sorry” (Trouble Man: Heavy Is The Head)

AM: T.I. sounds like he raps with his teeth clenched the entire time. But never mind what the blogs say, you know? Tip brings along an angry beat that Jazzie Pha tosses some reflective piano on. André 3000 sounds amazing, spitting in double time, easing up, and warbling. He gets seriously contemplative, apologizing to his Mom and Big Boi, thinking back on his life, wondering if it’s been worth it and why he acted so strangely. Compelling, wise stuff--André probing his psyche like Big does on “Descending.” André also complains about internet music critics. “Boring, really?” Seriously, who could find this boring? 5/5

NS: Poor T.I. was destined for second place before he even started, as even he acknowledged in interviews about "Sorry". Backed by an odd, piano-based beat, André 3000 begins his verse with a bounce in his lyrical step, unleashing words at such a fast clip that it seems unbelievable how much he pauses. Content-wise, "Sorry" finds 3000 feeling even more forlorn and pessimistic than usual. Admitting, "I used to be a way better rapper and writer when I used to want to rap," Dré apologizes to his mother and his "rap partner" in turn, admitting his retreat into hermitry was born of music writers like ourselves paying such close attention to his verses. Is he fair to us? If anything, he pulls his punches. "Boring, really?" he asks. The incredulous reaction is mutual, André. 5/5

[See here for last year's Rockaliser 3000 Beatdown, and here for our opinions on the latest Big Boi.]

Monday, December 31, 2012

Sunday, December 23, 2012

Beyond "Maggot Brain": Eddie Hazel's Other Greatest Solos

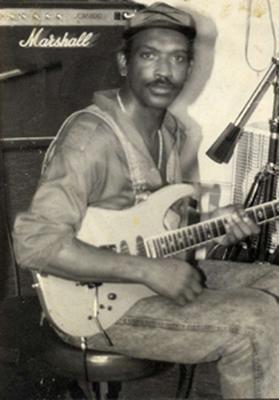

December 23, 2012 marks 20 years since the death of legendary Funkadelic guitarist Eddie Hazel. Many years ago, I wrote this about the still-incendiary "Maggot Brain," an extended guitar solo off Funkadelic's third album that ranks among the best solos ever recorded:

While Hazel is still defined mostly as the instrumental powerhouse behind "Maggot Brain" (and to a lesser extent, as a primary songwriter in the early days of Parliament and Funkadelic), this has unfortunately led fans of Hazel, including myself, to ignore his many other accomplishments as a guitarist and recording artist. Hazel is a clear factor on Funkadelic's first three albums Funkadelic, Free Your Mind... and Maggot Brain, and along with his solo work and collaborations with other artists in the P-Funk aegis, he has recorded a body of work that is at least as large as, say, Hendrix's. With this in mind, I wanted to provide any curious Hazel fans with a list of what to check out next, after "Maggot Brain." Here are five of my choices.

Eddie Hazel, "Lampoc Boogie," Jams From the Heart EP

This extended instrumental guitar boogie, originally available on Hazel's 1994 EP Jams From the Heart, clocks in at even longer than "Maggot Brain" (11:55) but the tone of these two solos could not be more different. Though they both pay tribute in different ways to Hendrix, a bottomless well of guitar inspiration for so many, "Lampoc Boogie" is limber and boisterous where "Maggot Brain" was portentous and elegiacal. Hazel's guitar melodies, played with such dexterity and breathtaking imagination, rumble and roar along to a simple bass-drum gallop that is just as astonishing for its simple, steady nature. In the grand tradition of other Hazel guitar jams, there's a fake fadeout, too.

Axiom Funk, "Pray My Soul," Funkcronomicon

This track, which comes from a compilation of various P-Funk contributions curated by Bill Laswell called Funkcronomicon, shows Hazel at his most reverent and austere. Once again taking his cue over a crisp four-chord rhythm guitar progression ("Maggot Brain" was also four chords), Hazel makes the most of the song's five minutes--he swoops and circles around simple blues chord patterns, bending the strings on his guitar like they represented a gateway to higher expression. "Pray My Soul" is a song that shows Hazel as the type of artist who values emotion and ingenuity over proficiency and skill, always.

Funkadelic, "Good Thoughts, Bad Thoughts," Standing On the Verge of Getting It On

By the time George Clinton and co. started recording Standing On the Verge of Getting It On, Hazel's influence on Funkadelic began to lessen. This would continue to be the case later into the 70s, especially as additional P-Funk guitarists Garry Shider and Michael Hampton began to pick up some of the slack for an increasingly-absent Hazel. And yet I ultimately think of this album as ultimately Hazel's, as much as that classic first three LP punch. Part of the reason for this is the album's final track "Good Thoughts, Bad Thoughts," a nine-minute slow burner that acts as the ultimate elegy to Funkadelic's early, most brilliant stage. Even with extremely talented instrumentalists like Shider and Hampton demonstrating their ample chops on future records, there was still something about Eddie's playing that could not be improved upon, or duplicated.

Funkadelic, "Miss Lucifer's Love," America Eats Its Young

This song, a tribute to the Beatles' harmonies at their most psychedelic, showcases Hazel's bizarre, unpredictable side, especially beginning at 2:43. Hazel lays down a thick, wah-heavy riff, spitting out bits of amazingly sculpted mini-melodies that distinguish themselves even over backing vocals that take much higher prominence in the mix. Drugs took their toll on Hazel's creativity and health, but it is hard to deny that, when he was on, few could match his escapes into the deepest recesses of guitar psychedelia, and he may not have reached those initial creative heights without drugs to provide the gateway. This is possibly another reason why his talent marked him for tragedy from a young age.

Parliament, "I Call My Baby Pussycat," Osmium

Hazel definitely had less of an influence on the Parliament sound than he would on Funkadelic, but he was definitely at his best on Parliament's forgotten 1970 debut, Osmium. Over one of Clinton's least subtle innuendos ever, Hazel taps on his fretboard like he's playing morse code, churning out a short but memorable solo in between the process of laying out a more standard wah groove. "I Call My Baby Pussycat" also showcases Eddie Hazel's best rhythm guitar playing, a mode for which he was always unappreciated. As he was in so many ways, and probably will continue to be, for a long time to come.

For the ten minutes and eighteen seconds that constitute this track, Eddie Hazel attacks, commands, and distorts one's emotions in a way only few artists can claim to do. Throughout the rest of his recording career, going through his solo album Games, Dames, & Guitar Things (which I recommend if you can get a copy from Rhino), he would contribute uniformly excellent guitar leads, alternately dazzling in their technical ability and emotionally taxing, yet in the end it all comes down to "Maggot Brain." Few artists have been so defined by one book, or one painting, or one movie, let alone one ten-minute electric guitar solo. It is his ultimate triumph and, considering his later output, his tragedy.

While Hazel is still defined mostly as the instrumental powerhouse behind "Maggot Brain" (and to a lesser extent, as a primary songwriter in the early days of Parliament and Funkadelic), this has unfortunately led fans of Hazel, including myself, to ignore his many other accomplishments as a guitarist and recording artist. Hazel is a clear factor on Funkadelic's first three albums Funkadelic, Free Your Mind... and Maggot Brain, and along with his solo work and collaborations with other artists in the P-Funk aegis, he has recorded a body of work that is at least as large as, say, Hendrix's. With this in mind, I wanted to provide any curious Hazel fans with a list of what to check out next, after "Maggot Brain." Here are five of my choices.

Eddie Hazel, "Lampoc Boogie," Jams From the Heart EP

Axiom Funk, "Pray My Soul," Funkcronomicon

Funkadelic, "Good Thoughts, Bad Thoughts," Standing On the Verge of Getting It On

Funkadelic, "Miss Lucifer's Love," America Eats Its Young

Parliament, "I Call My Baby Pussycat," Osmium

Friday, December 14, 2012

Vicious Lies Beatdown

1. Ascending

AM: "If ya'll don't know me by now, ya'll ain't gon never know me," Big Boi intones on the moody intro, whose shimmering acoustic guitar we'll hear again. It's an interesting opening statement for an album of left turns. 3.5/5

NS: Big Boi's latest kicks off with some rich acoustic picking, pretty swirling background vocals, and a few drags of the snare. It's not unpleasant, but it's hardly a "Feel Me (Intro)." This production will return later in the record, to better effect. 2/5

2. The Thickets feat. Sleepy Brown

AM: A solid Organized Noise beat twinkles and pulses, thick with bass and trapped-out drums. Big extolls his own greatness throughout. Not one of his 10 greatest verses or anything, but as he spits about being "truly one of the the baddest motherfuckers to ever do it" he's proving his point as he makes it. Not sure where these thickets are, but I'd chill there. 4/5

NS: A Big Boi album without a single Organized Noize production would be a very sad thing. Luckily, Sleepy Brown is on deck to croon his way through the cracks of this slow, deep bass rumbler. Big's verses showcase the rapper at his jumpiest and most unpredictable. After more than 20 years, ON's production style is still so thick and concrete, you can glide over the eddies of smooth grooves. 4/5

3. Apple Of My Eye

NS: A Big Boi album without a single Organized Noize production would be a very sad thing. Luckily, Sleepy Brown is on deck to croon his way through the cracks of this slow, deep bass rumbler. Big's verses showcase the rapper at his jumpiest and most unpredictable. After more than 20 years, ON's production style is still so thick and concrete, you can glide over the eddies of smooth grooves. 4/5

3. Apple Of My Eye

AM: Longtime collaborator David "Mr. DJ" Sheats is on the boards here, building things around a guitar that sounds like it was transported to Stankonia from a Peter, Bjorn & John song. Jake Troth, an uncredited songwritery guy, provides the hook--a little jarring at first, but it works. Give it a couple listens--Big is lithe on the mic, and Mr. DJ sprinkles his magic throughout, especially in the last minute. 4.5/5

NS: OutKast's third member Mr. DJ takes the production reins here, turning up the speed slightly yet reining back the tension on VLADR's first immediate masterpiece. "Apple" begins with Morricone-esque harmonics between keyboard and wooze guitar, and snaps to attention with a behind-the-beat guitar shuffle not too removed from Big's previous "Tambourine." The horns at the end seal the deal. 5/5

4. Objectum Sexuality feat. Phantogram

AM: One of three Phantogram collaborations on VLADR, which might have you wondering: did Sir Lucious Left Foot lose a bet with Phantogram's manager? Sarah Barthel's voice is a ghostly presence in Big Boi's world, but her hooks are a good fit for the darker, slower productions. The beat, Phantogram's, is pretty cool, like what an Earthtone III production might sound like if you sent it through fiber optic cables on the ocean floor. 4/5

NS: The first of what will be several bleak, slower songs, "Objectum" has a bizarre, stop-start structure and even weirder sound effects, but Big Boi finds a lyrical way through the electro clatter and weird violin samples. I'm not necessarily sold on Phantogram's chorus, but I dig the way it builds after the bridge. 4/5

5. In The A feat. T.I. & Ludacris

NS: OutKast's third member Mr. DJ takes the production reins here, turning up the speed slightly yet reining back the tension on VLADR's first immediate masterpiece. "Apple" begins with Morricone-esque harmonics between keyboard and wooze guitar, and snaps to attention with a behind-the-beat guitar shuffle not too removed from Big's previous "Tambourine." The horns at the end seal the deal. 5/5

4. Objectum Sexuality feat. Phantogram

AM: One of three Phantogram collaborations on VLADR, which might have you wondering: did Sir Lucious Left Foot lose a bet with Phantogram's manager? Sarah Barthel's voice is a ghostly presence in Big Boi's world, but her hooks are a good fit for the darker, slower productions. The beat, Phantogram's, is pretty cool, like what an Earthtone III production might sound like if you sent it through fiber optic cables on the ocean floor. 4/5

NS: The first of what will be several bleak, slower songs, "Objectum" has a bizarre, stop-start structure and even weirder sound effects, but Big Boi finds a lyrical way through the electro clatter and weird violin samples. I'm not necessarily sold on Phantogram's chorus, but I dig the way it builds after the bridge. 4/5

5. In The A feat. T.I. & Ludacris

AM: Twisting a line from Sir Lucious Left Foot's "Shutterbugg" into its hook, this slow-motion banger with its martial horn is a sort-of sequel to that album's "Patton." I'm pleasantly surprised by Ludacris' verse, but Tip's presence--he's OK, not at his best--brings to mind this year's "Sorry" (featuring André 3000, dearly missed here) and "Big Beast," both better songs than this. Not that "A" won't sound great blaring from your car speakers. 4/5

NS: The sample is a prominent swipe from "Shutterbugg," but the strutting, triumphalist monster beat is closer etymologically to Sir Lucious' "General Patton." All three Atlanta emcees prove themselves up to the challenge of honoring the tone of this gnarly head nodder, and demonstrate sickening amounts of hubris in the process, but it is Ludacris' swerving, dive-bombing style that is most ideally and hilariously suited to the track's killer rhythms. 5/5

6. She Hates Me feat. KiD CuDi

NS: The sample is a prominent swipe from "Shutterbugg," but the strutting, triumphalist monster beat is closer etymologically to Sir Lucious' "General Patton." All three Atlanta emcees prove themselves up to the challenge of honoring the tone of this gnarly head nodder, and demonstrate sickening amounts of hubris in the process, but it is Ludacris' swerving, dive-bombing style that is most ideally and hilariously suited to the track's killer rhythms. 5/5

6. She Hates Me feat. KiD CuDi

AM: The spacious, mid-tempo beat doesn't give Daddy Fat Sacks a lot to chew on, though he's got a lot on his mind, and he yawns this one out. One of the limpest beats to ever feature Big Boi. It doesn't help that the subject matter skirts close to "Ms. Jackson" territory, without that joint's electric charge. I could have done without Kid Cudi. 2.5/5

NS: In another proud OutKast tradition, "She Hates Me" is VLADR's first emotionally overwhelming number. Kid Cudi deserves credit for the hook, a romantic lament that turns hostile halfway through. Big Boi's skills here are as impressive here as ever--he's more controlled than usual, but the way he lags slightly behind the beat and enunciates the end of each phrase is fantastic. 5/5

NS: The first of two songs that mention the youngest Wilbury, "Thom Pettie"'s highlight is Killer Mike's killer verse, which delves into sexual particulars in a manner that R.A.P. Music never really got to. This is another song with a weird start-stop structure, but Yukimi Nagano's voice and cleanly distorted guitar solos ably fill in some of the blanks. 4/5

9. Mama Told Me feat. Kelly Rowland

AM: The Flush--they of Big's "Royal Flush" and "Be Still" by Janelle Monae (where is she?)--run a funky, vocoder-laden Sir Lucious beat through a translucent purple Gameboy Color. Which is fine, really good actually--the drums sound like Prince programmed them--though I wish it hit a little harder. 4/5

NS: When this video with Little Dragon first came out, I wondered if "Mama Told Me" was destined to be the next "Hey Ya"-level superhit. Guess not, but this song feels like such a single, if that makes any sense. Deviating from previous rap odes to mothers ("Dear Mama," "Hey Mama"), which were basically apologies, Big exults in the pride of fulfilling his mama's long-held expectations, as bubbly synths chirp in, as if in affirmation. 5/5

10. Lines feat. A$AP Rocky & Phantogram

NS: In another proud OutKast tradition, "She Hates Me" is VLADR's first emotionally overwhelming number. Kid Cudi deserves credit for the hook, a romantic lament that turns hostile halfway through. Big Boi's skills here are as impressive here as ever--he's more controlled than usual, but the way he lags slightly behind the beat and enunciates the end of each phrase is fantastic. 5/5

7. CPU feat. Phantogram

AM: I'm not a big fan of that last joint, but the sequencing in the middle of the album is pretty great--the song with the hook "it's you that's on my computer screen/cuz it's you that's on my mind" follows the relationship problems one. That might sound porn-y, but that's not what "CPU" aims for. Not that Big doesn't get lurid on this album--he does, plenty, before and after this--but Phantogram program the chilly "CPU." Love the guitar at the end. 4/5

NS: Phantogram returns, just in time for the album to dip into full tilt "sad dance music." At first this nu-technology anthem doesn't seem best suited for Big Boi's talents, and indeed as far as those things go, I prefer Andre 3000's verse on 1998's "Synthesizer." But when the beat picks up, there's no denying its spacey yet subterranean propulsiveness. 3.5/5

8. Thom Pettie feat. Little Dragon & Killer Mike

AM: I'm not a big fan of that last joint, but the sequencing in the middle of the album is pretty great--the song with the hook "it's you that's on my computer screen/cuz it's you that's on my mind" follows the relationship problems one. That might sound porn-y, but that's not what "CPU" aims for. Not that Big doesn't get lurid on this album--he does, plenty, before and after this--but Phantogram program the chilly "CPU." Love the guitar at the end. 4/5

NS: Phantogram returns, just in time for the album to dip into full tilt "sad dance music." At first this nu-technology anthem doesn't seem best suited for Big Boi's talents, and indeed as far as those things go, I prefer Andre 3000's verse on 1998's "Synthesizer." But when the beat picks up, there's no denying its spacey yet subterranean propulsiveness. 3.5/5

8. Thom Pettie feat. Little Dragon & Killer Mike

AM: A wobbly, almost dubby street cut. Big takes the first verse, switching up his flow several times. Little Dragon have the middle third, and send the song deep into blunt-rolling territory. Batting third, Killer Mike is amazing, his verse as good as anything he spit on this year's R.A.P. Music. Maybe the best verse on the entire album. 4.5/5

NS: The first of two songs that mention the youngest Wilbury, "Thom Pettie"'s highlight is Killer Mike's killer verse, which delves into sexual particulars in a manner that R.A.P. Music never really got to. This is another song with a weird start-stop structure, but Yukimi Nagano's voice and cleanly distorted guitar solos ably fill in some of the blanks. 4/5

9. Mama Told Me feat. Kelly Rowland

AM: The Flush--they of Big's "Royal Flush" and "Be Still" by Janelle Monae (where is she?)--run a funky, vocoder-laden Sir Lucious beat through a translucent purple Gameboy Color. Which is fine, really good actually--the drums sound like Prince programmed them--though I wish it hit a little harder. 4/5

NS: When this video with Little Dragon first came out, I wondered if "Mama Told Me" was destined to be the next "Hey Ya"-level superhit. Guess not, but this song feels like such a single, if that makes any sense. Deviating from previous rap odes to mothers ("Dear Mama," "Hey Mama"), which were basically apologies, Big exults in the pride of fulfilling his mama's long-held expectations, as bubbly synths chirp in, as if in affirmation. 5/5

10. Lines feat. A$AP Rocky & Phantogram

AM: A cool Organized Noise beat--it sounds like they took the album's street single, and sliced up the keys and vocal lines into tiny little strips. Never thought I'd see A$AP Rocky on a Big Boi album, but he does himself proud. Big appears for less than a minute on his own 3:30 cut. He sounds pretty good, doesn't give himself nearly enough time to get going. 4/5

NS: Harlem rapper (and personal favorite) A$AP Rocky slots effortlessly into the VLADR aesthetic, throwing in a few vocal southernisms while retaining his distinctly New York identity via blisteringly quirky versage. Phantogram's chorus (them again!) is a slight momentum killer--this is yet another stop-start arrangement--but Rocky and Big complement each other so naturally, the rest is acceptable noise. 4.5/5

11. Shoes For Running feat. B.o.B. & Wavves

NS: Harlem rapper (and personal favorite) A$AP Rocky slots effortlessly into the VLADR aesthetic, throwing in a few vocal southernisms while retaining his distinctly New York identity via blisteringly quirky versage. Phantogram's chorus (them again!) is a slight momentum killer--this is yet another stop-start arrangement--but Rocky and Big complement each other so naturally, the rest is acceptable noise. 4.5/5

11. Shoes For Running feat. B.o.B. & Wavves

AM: Confusing collaborations with rock musicians are a part of hip-hop's very fabric. Big has more than a few on this album, which the material mostly justifies. But this is where I draw the line. B.o.B. prattles on about nothing, Wavves whines out a mall-punk hook, and then and a chorus of children imitate Wavves (really). It's a shame, because Big's first verse is great. 2/5

NS: I have no idea what Wavves' chorus is about--running away from death?--and B.o.B.'s verse doesn't do much besides pass time. But the kids chorus turns out to be a genius effect, and the song's chugging guitar and whistled vocals combine to overcome the sum of parts elsewhere. Ultimately, the evolving groove and Big's verse are what makes this track work. 3.5/5

12. Raspberries feat. Mouche & Scar

NS: I have no idea what Wavves' chorus is about--running away from death?--and B.o.B.'s verse doesn't do much besides pass time. But the kids chorus turns out to be a genius effect, and the song's chugging guitar and whistled vocals combine to overcome the sum of parts elsewhere. Ultimately, the evolving groove and Big's verse are what makes this track work. 3.5/5

12. Raspberries feat. Mouche & Scar

AM: Easily the weirdest thing here, the drone-soul of "Raspberries" is built around a two-chord keyboard oscillation that wouldn't sound out of place on a Sterolab album. Mouche, Scar and Big weave their voices together, and we're treated to Antwan Patton's loverman warble. Pshyched out, and cooler than a polar bear's toenail. 4.5/5

NS: VLADR's pace slows considerably on this track, and stays at a similar level for the rest of the record. On "Raspberries," Big Boi sings more than he raps, in a call-and-response arrangement with either Mouche or Scar (I have no idea which). The song is again about sexual conquest, but the tone is dire and downbeat, as if Big is losing interest in repeating such stories. 3/5

13. Tremendous Damage feat. Bosko

AM: The penultimate track's a reflective ballad, a bit like SLLF:TSOCD's "The Train, Pt. 2." I like the verses, but this could use the Southern flourishes of "Train." Bosko's chorus borders on dull, and the beat doesn't get exciting until the last minute. Like so many of these songs, what it needs is more Big Boi, and a little more funk. 3/5

NS: The piano melody is amateur stuff, and it never really develops, and yet somehow the song affects. Part of it is the ruminative nature of Big's words, especially in the section where he discusses his deceased father, the first "Dusty Chico" who served in Vietnam. Even when the song is gentle, there's a hard-edged tinge to Big's subject matter--it's a song about growing up and gaining perspective, and it takes a lot of musical chances to make some interesting points. 4/5

14. Descending feat. Little Dragon

NS: VLADR's pace slows considerably on this track, and stays at a similar level for the rest of the record. On "Raspberries," Big Boi sings more than he raps, in a call-and-response arrangement with either Mouche or Scar (I have no idea which). The song is again about sexual conquest, but the tone is dire and downbeat, as if Big is losing interest in repeating such stories. 3/5

13. Tremendous Damage feat. Bosko

AM: The penultimate track's a reflective ballad, a bit like SLLF:TSOCD's "The Train, Pt. 2." I like the verses, but this could use the Southern flourishes of "Train." Bosko's chorus borders on dull, and the beat doesn't get exciting until the last minute. Like so many of these songs, what it needs is more Big Boi, and a little more funk. 3/5

NS: The piano melody is amateur stuff, and it never really develops, and yet somehow the song affects. Part of it is the ruminative nature of Big's words, especially in the section where he discusses his deceased father, the first "Dusty Chico" who served in Vietnam. Even when the song is gentle, there's a hard-edged tinge to Big's subject matter--it's a song about growing up and gaining perspective, and it takes a lot of musical chances to make some interesting points. 4/5

14. Descending feat. Little Dragon

AM: "Tremendous Damage" morphs into "Descending" smoothly, and all of a sudden we're back to the guitar waves of the intro. Yukimi Nagano's wail and Big Boi's warble float in the song's ether, getting heavy. Here's a weird, regretful, almost new agey cut that keeps both feet planted in OutKast's universe. No small feat. 4.5/5

NS: As promised, the creamy acoustic arpeggios of "Ascending" have returned, adorned with ghostly spiritual soundscapes courtesy of Little Dragon. Big Boi once again returns to the subject of his father, even going so far as to croon desperately "My daddy's gone," in what is likely the album's darkest moment. "Descending" is an austere track, but it builds into something refined and stately, a radical inversion of the casual boast song. It would only work as an ender on an album of this caliber. 4.5/5

Nathan's average score was 4.1, Aaron's was 3.8. Expect another OutKast-related Beatdown in this space in the near future. If you're feeling nostalgic, check out our Beatdown of Big Boi's first solo album.

NS: As promised, the creamy acoustic arpeggios of "Ascending" have returned, adorned with ghostly spiritual soundscapes courtesy of Little Dragon. Big Boi once again returns to the subject of his father, even going so far as to croon desperately "My daddy's gone," in what is likely the album's darkest moment. "Descending" is an austere track, but it builds into something refined and stately, a radical inversion of the casual boast song. It would only work as an ender on an album of this caliber. 4.5/5

Nathan's average score was 4.1, Aaron's was 3.8. Expect another OutKast-related Beatdown in this space in the near future. If you're feeling nostalgic, check out our Beatdown of Big Boi's first solo album.

Friday, August 31, 2012

Humpty Hump's Head

In a parking garage in East Oakland’s Jingletown neighborhood, an enormous piece of local music history gazes out at parked cars. More than ten feet tall, and sporting sunglasses, the relic is a stage prop modeled after rapper Shock G. The head was featured in a 1993 music video by rapper Shock G’s platinum-selling group, Digital Underground, and went out with the group on tour. Now it collects dust and dirt from exhaust pipes.Rockaliser readers may be interested to know that I reported on the above, for the website Oakland North. You can click over there, for the whole thing. It's not criticism, but do you really need to be reminded how great Sex Packets is? I'll be writing quite a bit on Oakland North in the coming months. Mostly, it won't be music related, but I'll let folks know via the blog or our Twitter if/when any music-related stuff surfaces over there.

Anyways, this was a pretty fascinating subject to devote many hours of my life to. It even involved an interview with Shock G (over email), the Digital Underground maestro himself. The fate of this enormous prop head makes you wonder what ever became of the Pink Floyd pigs (created by the same people who built the Humpty Hump head), or the Beastie Boys cock.

Friday, August 24, 2012

Jody Rosen and the People's List

Slate's pop music critic Jody Rosen is an occasional guest on the Culture Gabfest, a weekly podcast put out by the online magazine which features weekly cultural discussions between movie critic Dana Stevens, deputy editor Julia Turner and critic-at-large Stephen Metcalf. A couple of years ago, they devoted a segment of their show to a discussion about a candid John Mayer interview in Playboy. At the beginning of the segment, Rosen attempts to bring audiences up to speed on who Mayer is and what type of music he plays. In the course of this, a minor disagreement between Rosen and Metcalf ensues.

Rosen seems to be one of those music critics who tends to view the act of listening to and enjoying music as secondary to the cultural experience of being a "music listener"--in other words, he's more interested in music fandom as a badge of status than he is in listening to anything for the art or pleasure itself. Of course, Rosen pretends to be all about "pleasure"--the music he listens to is inherently more pleasurable because it is popular and on the radio, seems to be the argument--but he also spends an awful amount of time chiding fellow Brooklynites for not sharing his cosmopolitan, "poptimist" aesthetics as enthusiastically as he does. In fact, he seems to do a lot more of that these days than he does, well, reviewing music. To Rosen, honest aesthetic differences in the case of pop, R&B or country bely creeping racist, classist, or sexist resentments. If we were really being honest about what we'd like, he argues, we would listen to Brad Paisley and the Black-Eyed Peas, but "artsy-fartsy rocker types" (one of Rosen's terms for music listeners who don't precisely share his tastes) are terrified of being caught enjoying something popular. In fact, in Rosen's world it seems like music fans are a constantly-cowed, terrified bunch, obsessively weighing their tastes against others in bids to see who can agree the most with the narrow sociocultural niche-consensus. Ironically, that description seems to more accurately fit Rosen himself. This isn't music criticism, it's just "criticism" untethered to any set of tastes and cultural presumptions other than nihilistic political gamesmanship and Internet social-climbing.

Yesterday, Rosen wrote a piece for Slate about Pitchfork's recent People's List, an audience poll sponsored by Converse. Nearly 28,000 participants voted on and ranked their 100 favorite albums between 1996 and 2011, and the votes were then tabulated and displayed in all sorts of useful demographic categories. The overall results were fairly predictable and surprise-free, as one expects from committee votes. Who cares if Radiohead tops another list? Jody did, and his contempt for the voters (of which he was one [so was I]) and their aggregated list of choices was swift and damning:

Rosen goes on to take obligatory shots at Pitchfork and its readers ("as much a niche publication as XXL, or Cat Fancy") before turning his eye at the True Problem, which is the lack of gender diversity. Of the top 200 records voted by readers, only 23 were written or performed partially by women. This is probably the result of a complex interlocking of cultural factors, since Pitchfork readers aren't a representative sample of music listeners OR indie music listeners, and the 28,000 folks who voted aren't even representative of the average Pitchfork reader. Nevertheless Rosen cannot contain his righteous fury against those who had, by exclusion, wronged his favorite female artists:

Anyway, notice what's missing from Rosen's inclusive summation of "pop, R&B or country music fans"--hip-hop. Rosen knew very well to leave that genre out of this part of his argument (though he mentions it earlier when talking about race) because of course a survey of hip-hop's greatest albums would yield even fewer female artists than Pitchfork's list. By the same token, a list of country music's finest records may include more overall females, but short of Cowboy Troy and a few others the country list is liable to be more white-dominated than even Pitchfork's sans Kanye. The only way Rosen gets away with characterizing such an ill-defined group of people is by moving the goalposts for each genre preference--when he asks "where are the politics," that's really code for "why aren't my aesthetic tastes being reinforced by more people like me?" Music lovers who are actually comfortable with their tastes don't demand that they be approved by others, especially for political reasons. For Rosen, liking Radiohead and its ilk is evidence of oppression against the "Top 40's great unwashed," a view of casual music listeners that no music fan actually shares, other than in Rosen's paranoid imagination. Maybe one of his Slate colleagues (Will Saletan maybe?) should sit Rosen down and read him some Hofstadter.

It's really hard to say what bothers me most about this piece: its presumptuous diagnosis of "indie music fans," who are actually not a monolithic group; its patently unfair and incorrect characterization of indie "progressivism," which holds fans to an unfair standard that even then is inconsistently applied; its smug jokes about some of earth's easiest musical targets like Bon Iver; its unwillingness to consider counter-arguments, from the previously-mentioned hip-hop/gender disparity to the existence of identical sampled results from female Pitchfork readers, who also placed white male-written OK Computer at the top of the consensus heap; the fact that this is overall an argument for tokenism, and the demonization of honest expressions of opinions.

But I guess what most bothers me is when he says the Pitchfork list is a "scandal." Really, a list that aggregates the musical choices of .0001% of the population of the US and presents it in various useful, colorful charts and graphs, is a scandal?

I think and write a lot about music and politics. You know what is actually a scandal? It's a scandal that, in the wake of the massive French media conglomerate Vivendi buying EMI last year, there are only three major record companies controlling (and often limiting) the output of thousands of artists. I think it's a scandal the Department of Justice, after only a year's worth of investigation, approved the merger of Live Nation and Ticketmaster--the DOJ's solution to the inevitable monopoly was a worthless mandate that the company "create" two of its own business rivals. Along those lines, I also think it's a scandal that Ticketmaster-Live Nation can basically buy the support of politicians like Rahm Emmanuel. I think it's a scandal that music education, and the arts in general, are no longer a priority in public schools, and while no politician ever seriously considers this idea it seems long past time that affordable instruments were made a priority for children in low-income communities. I think it's a scandal that aspiring professional musicians on Broadway and elsewhere are losing live gig opportunities to penny-pinching producers who cut live music out of the equation via prerecorded tapes and mp3s. When I walk past a street performer in Manhattan, I often think of how scandalous it is that Bloomberg gets away with charging buskers a $250 fine for being within 50 feet of any city-designated monument. And that's just for a first-time offense.

I think it's a scandal that payola still exists in the 21st century, ensuring the sometimes-awful music that Rosen admires remains on the radio, and to me it is infinitely scandalous (and suspicious) that the one governor who actively prosecuted payola (and Wall Street) fraud was busted in a prostitution scandal and mocked by Rosen's colleagues at Slate for not realizing that corporations mandating a pre-selected set of tunes is just the Way Things Are. It is especially scandalous and pathetic how the FCC rolls over for the RIAA and anyone else rich enough to lobby Orrin Hatch. It also bothers me, though I try not to lose any sleep about it, that "indie" has just become another brand word for publicists, and that people who complain about this are derided by fake, usually white populists as "elite" or "Fair Trade espresso-swilling."

What else? The sampling laws in this country are scandalous, responsible for insane fines and nonsensical legal barriers against legitimate creative expression. It also seems to me scandalous (if not necessarily illegal) that the few Jay-Z-Kanye level artists who can afford to pay for high-profile samples buy them directly from the record companies, and don't consult with the artists themselves. It is horrifying to me that an artist can refuse to put his or her song in a commercial, only to turn on the TV and hear what is essentially a copycat version of that artist. It is scandalous that the RIAA still charges a $150,000 fine for the crime of downloading one 99 cent song. These are just a few musical/"political" matters that bother me a bit more than how many female or black artists a certain ill-defined group of people put in their top 10.

Yet Rosen never reports about any of these issues for Slate or Rolling Stone--he's too busy mocking liberals for their intentions in the Slate-est of manners, smugly characterizing folks like Springsteen as classist poseurs for dealing in some Occupy-type language ("painting WPA murals" he calls it). Much of what Rosen has written for Slate or Rolling Stone suggests he is a proud, active defender of the corporate status quo. That he chides others for their lack of "progressivism," and then looks upon himself as a model of cosmopolitan music fandom is as insulting as it is refutable. Perhaps with this article, those critical of indie fandom will discover how "poptimists" are in fact just as capable of smug, judgmental observations as the artsy-fartsy types or "rockists" who hate on the Top 40 "unwashed masses."

I don't dislike Jody Rosen as a writer, I don't want him fired or anything like that. Unfortunately, he's playing the Internet discourse game*, where manufactured outrage over the most asinine of issues is retweeted thoughtlessly by people who like to see their narrow worldview reinforced, never challenged. Rosen defends his piece by saying that, so far, only men have criticized it. Since women haven't, that somehow makes it more legitimate. This is how a writer who can't actually defend his or her arguments deflects criticism, by talking up the people who parrot it uncritically.

By being demonstrably obsessed with the measure of his opinions against others, Rosen is as much a creature of "indie" close-mindedness as those unwashed mashes he mocks. To me, as harsh as that sounds, that's at least a partial definition of a "hack"--someone who fits their opinion around a preconceived political narrative. And it is a common tendency amongst paid music critics. I get it, I took Sociology 101, so I understand there is something called "white privilege" that exists. Now, does pointing that out constantly actually enhance anyone's understanding of the Vampire Weekend album?

Sometimes I wonder if there's anyone left on the Internet with an honest opinion.

*As I am now, way ahead of you.

Rosen: But just a little word of background about John Mayer...he is, for the record, not only good in technical terms--in technical terms he's a great musician, he's a great guitar player. He sort of instantly achieved this, you know, muso-wanker status right up there with Clapton and those guys. He is a sort of a "classic rock level guitarist" and is regarded as such. You know, he's constantly...the Police have him on stage to play with them. He's that sort of level of player, like a Mark Knopfler-style dude. Considered very cheesy by hipsters because of that. So it's not...

Metcalf: That...that cannot be the reason that hipsters regard him as cheesy.

Rosen: No, but...

Metcalf: It has to be his status as Dave Matthews-lite, right? I mean...his awful singing voice...sorry.

Rosen: ...I just want to complete the thought.Of course he doesn't. It's a mostly unnecessary remark, and even if it wasn't such a cliche it would still add nothing to the discussion. Metcalf rightfully points to logical lapses in this blanket statement about "hipsters," and Rosen calmly ducks the rejoinder by talking up the cheesiness of "Your Body Is a Wonderland." Later, Rosen admits, "I'm not a fan of John Mayer's music at all. I am a fan, however, of John Mayer the celebrity, which is its own distinct thing."

Rosen seems to be one of those music critics who tends to view the act of listening to and enjoying music as secondary to the cultural experience of being a "music listener"--in other words, he's more interested in music fandom as a badge of status than he is in listening to anything for the art or pleasure itself. Of course, Rosen pretends to be all about "pleasure"--the music he listens to is inherently more pleasurable because it is popular and on the radio, seems to be the argument--but he also spends an awful amount of time chiding fellow Brooklynites for not sharing his cosmopolitan, "poptimist" aesthetics as enthusiastically as he does. In fact, he seems to do a lot more of that these days than he does, well, reviewing music. To Rosen, honest aesthetic differences in the case of pop, R&B or country bely creeping racist, classist, or sexist resentments. If we were really being honest about what we'd like, he argues, we would listen to Brad Paisley and the Black-Eyed Peas, but "artsy-fartsy rocker types" (one of Rosen's terms for music listeners who don't precisely share his tastes) are terrified of being caught enjoying something popular. In fact, in Rosen's world it seems like music fans are a constantly-cowed, terrified bunch, obsessively weighing their tastes against others in bids to see who can agree the most with the narrow sociocultural niche-consensus. Ironically, that description seems to more accurately fit Rosen himself. This isn't music criticism, it's just "criticism" untethered to any set of tastes and cultural presumptions other than nihilistic political gamesmanship and Internet social-climbing.

Yesterday, Rosen wrote a piece for Slate about Pitchfork's recent People's List, an audience poll sponsored by Converse. Nearly 28,000 participants voted on and ranked their 100 favorite albums between 1996 and 2011, and the votes were then tabulated and displayed in all sorts of useful demographic categories. The overall results were fairly predictable and surprise-free, as one expects from committee votes. Who cares if Radiohead tops another list? Jody did, and his contempt for the voters (of which he was one [so was I]) and their aggregated list of choices was swift and damning:

In short, nothing about this list is surprising, and for those of us who love pop music in its many flavors and permutations--including pop music that is actually popular--the usual complaints apply. Aesthetically, generically, regionally, racially, "The People's List" is narrow and conservative. Pitchfork's readers ignored virtually every musical genre other than indie rock and its folk- and electronic-offshoots. The Top 40 scarcely registers a blip in this world. Hip-hop--and for that matter--Afro-America--is represented mainly by Kanye West. (Kanye contains multitudes, but c'mon.) Country music doesn't exist. Metal doesn't exist. Reggaeton, bachato, salsa? ¿Como? The word outside the United States--it's barely there. The United States, Canada, and the UK account for 174 of the 200 albums; the only non-Anglophone nations are France and Sweden.Give Rosen some credit--he does leave the words "hipster," "rockist," and "pretentious" out of the discussion, thank Christ (I'd like to think us unpaid Rockaliser bloggers have down our part to shame critics into calming down on that a bit).

Rosen goes on to take obligatory shots at Pitchfork and its readers ("as much a niche publication as XXL, or Cat Fancy") before turning his eye at the True Problem, which is the lack of gender diversity. Of the top 200 records voted by readers, only 23 were written or performed partially by women. This is probably the result of a complex interlocking of cultural factors, since Pitchfork readers aren't a representative sample of music listeners OR indie music listeners, and the 28,000 folks who voted aren't even representative of the average Pitchfork reader. Nevertheless Rosen cannot contain his righteous fury against those who had, by exclusion, wronged his favorite female artists:

Still--what the hell is wrong with these dudes? Did it escape their attention that for much of the past decade and a half, female artists have had a stranglehood on the popular music zeitgeist? Have they never heard of Missy Elliott? Can they really prefer The National to M.I.A.'s Kala, to Bjork's Homogenic to Joanna Newsom's Ys? Where are the politics in all of this?My questions: what kind of "critic" compares his own aesthetic choices against some subjective, randomly-defined "cultural zeitgeist"? Why can't such choices be made openly and honestly without any regard whatsoever for the opinions of others? Yeah, Adele was huge--remind me again why I need to like her, other than that she is a woman and my list doesn't have enough female choices? Why not prefer the National to M.I.A. or Joanna Newsom, and why do you care? And why are "politics" only important to you when it comes to the taste of indie rockers? On that last point, Rosen believes he has stumbled upon a great political irony, worthy of Voltaire. Indie rock's conservative consensus picks don't gibe with the culture's progressive views on gender and race:

If you surveyed the roughly 24,600 men who submitted "People's List" ballots, I wager you'd find nearly 100 percent espousing progressive views on gender issues. This would not be the case if you took a similar survey of pop, R&B, or country music fans--yet a "People's List" of top recordings in those genres from 1996-2011 with a similar gender breakdown is unimaginable. The fact is, when it comes to the question of women and, um, art, the Top 40's great unwashed--and even red state Tea Party partisans--are far more progressive and inclusive than the mountain-man-bearded, Fair Trade espresso-swilling, self-styled lefties of indiedom. Portlandia, we have a problem.Red state Tea Party...Fair Trade espresso-swilling...Portlandia...sorry for nodding off, just nearly had cliche seizure.

Anyway, notice what's missing from Rosen's inclusive summation of "pop, R&B or country music fans"--hip-hop. Rosen knew very well to leave that genre out of this part of his argument (though he mentions it earlier when talking about race) because of course a survey of hip-hop's greatest albums would yield even fewer female artists than Pitchfork's list. By the same token, a list of country music's finest records may include more overall females, but short of Cowboy Troy and a few others the country list is liable to be more white-dominated than even Pitchfork's sans Kanye. The only way Rosen gets away with characterizing such an ill-defined group of people is by moving the goalposts for each genre preference--when he asks "where are the politics," that's really code for "why aren't my aesthetic tastes being reinforced by more people like me?" Music lovers who are actually comfortable with their tastes don't demand that they be approved by others, especially for political reasons. For Rosen, liking Radiohead and its ilk is evidence of oppression against the "Top 40's great unwashed," a view of casual music listeners that no music fan actually shares, other than in Rosen's paranoid imagination. Maybe one of his Slate colleagues (Will Saletan maybe?) should sit Rosen down and read him some Hofstadter.

It's really hard to say what bothers me most about this piece: its presumptuous diagnosis of "indie music fans," who are actually not a monolithic group; its patently unfair and incorrect characterization of indie "progressivism," which holds fans to an unfair standard that even then is inconsistently applied; its smug jokes about some of earth's easiest musical targets like Bon Iver; its unwillingness to consider counter-arguments, from the previously-mentioned hip-hop/gender disparity to the existence of identical sampled results from female Pitchfork readers, who also placed white male-written OK Computer at the top of the consensus heap; the fact that this is overall an argument for tokenism, and the demonization of honest expressions of opinions.

But I guess what most bothers me is when he says the Pitchfork list is a "scandal." Really, a list that aggregates the musical choices of .0001% of the population of the US and presents it in various useful, colorful charts and graphs, is a scandal?

I think and write a lot about music and politics. You know what is actually a scandal? It's a scandal that, in the wake of the massive French media conglomerate Vivendi buying EMI last year, there are only three major record companies controlling (and often limiting) the output of thousands of artists. I think it's a scandal the Department of Justice, after only a year's worth of investigation, approved the merger of Live Nation and Ticketmaster--the DOJ's solution to the inevitable monopoly was a worthless mandate that the company "create" two of its own business rivals. Along those lines, I also think it's a scandal that Ticketmaster-Live Nation can basically buy the support of politicians like Rahm Emmanuel. I think it's a scandal that music education, and the arts in general, are no longer a priority in public schools, and while no politician ever seriously considers this idea it seems long past time that affordable instruments were made a priority for children in low-income communities. I think it's a scandal that aspiring professional musicians on Broadway and elsewhere are losing live gig opportunities to penny-pinching producers who cut live music out of the equation via prerecorded tapes and mp3s. When I walk past a street performer in Manhattan, I often think of how scandalous it is that Bloomberg gets away with charging buskers a $250 fine for being within 50 feet of any city-designated monument. And that's just for a first-time offense.

I think it's a scandal that payola still exists in the 21st century, ensuring the sometimes-awful music that Rosen admires remains on the radio, and to me it is infinitely scandalous (and suspicious) that the one governor who actively prosecuted payola (and Wall Street) fraud was busted in a prostitution scandal and mocked by Rosen's colleagues at Slate for not realizing that corporations mandating a pre-selected set of tunes is just the Way Things Are. It is especially scandalous and pathetic how the FCC rolls over for the RIAA and anyone else rich enough to lobby Orrin Hatch. It also bothers me, though I try not to lose any sleep about it, that "indie" has just become another brand word for publicists, and that people who complain about this are derided by fake, usually white populists as "elite" or "Fair Trade espresso-swilling."

What else? The sampling laws in this country are scandalous, responsible for insane fines and nonsensical legal barriers against legitimate creative expression. It also seems to me scandalous (if not necessarily illegal) that the few Jay-Z-Kanye level artists who can afford to pay for high-profile samples buy them directly from the record companies, and don't consult with the artists themselves. It is horrifying to me that an artist can refuse to put his or her song in a commercial, only to turn on the TV and hear what is essentially a copycat version of that artist. It is scandalous that the RIAA still charges a $150,000 fine for the crime of downloading one 99 cent song. These are just a few musical/"political" matters that bother me a bit more than how many female or black artists a certain ill-defined group of people put in their top 10.

Yet Rosen never reports about any of these issues for Slate or Rolling Stone--he's too busy mocking liberals for their intentions in the Slate-est of manners, smugly characterizing folks like Springsteen as classist poseurs for dealing in some Occupy-type language ("painting WPA murals" he calls it). Much of what Rosen has written for Slate or Rolling Stone suggests he is a proud, active defender of the corporate status quo. That he chides others for their lack of "progressivism," and then looks upon himself as a model of cosmopolitan music fandom is as insulting as it is refutable. Perhaps with this article, those critical of indie fandom will discover how "poptimists" are in fact just as capable of smug, judgmental observations as the artsy-fartsy types or "rockists" who hate on the Top 40 "unwashed masses."

I don't dislike Jody Rosen as a writer, I don't want him fired or anything like that. Unfortunately, he's playing the Internet discourse game*, where manufactured outrage over the most asinine of issues is retweeted thoughtlessly by people who like to see their narrow worldview reinforced, never challenged. Rosen defends his piece by saying that, so far, only men have criticized it. Since women haven't, that somehow makes it more legitimate. This is how a writer who can't actually defend his or her arguments deflects criticism, by talking up the people who parrot it uncritically.

By being demonstrably obsessed with the measure of his opinions against others, Rosen is as much a creature of "indie" close-mindedness as those unwashed mashes he mocks. To me, as harsh as that sounds, that's at least a partial definition of a "hack"--someone who fits their opinion around a preconceived political narrative. And it is a common tendency amongst paid music critics. I get it, I took Sociology 101, so I understand there is something called "white privilege" that exists. Now, does pointing that out constantly actually enhance anyone's understanding of the Vampire Weekend album?

Sometimes I wonder if there's anyone left on the Internet with an honest opinion.

*As I am now, way ahead of you.

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

American R&B: Gospel Grooves, Funky Drummers and Soul Power (Out Now)

Check it out, I wrote a book!

American R&B: Gospel Grooves, Funky Drummers, and Soul Power

by Aaron Mendelson

Available Now From Lerner Publishing

Like Nathan, I've written an entry in Lerner Publishing's "American Music Milestones" series. It's called American R&B: Gospel Grooves, Funky Drummers, and Soul Power. The book is geared towards teenage readers, and I'd be delighted if it found its way into the hands of the budding music fan in your life.

American R&B was the result of a year spent immersed in the history and music of the genre, so I'd like to think it'd be an enjoyable and educational read for people outside of its intended age range. If you don't know how many pounds of sweat James Brown shed at each performance, you might learn something yourself.

In either case, I'd be thrilled to learn what you think of the book. It's a bit expensive--about $23 from Lerner's website, or $30 at Amazon--due to the book's binding, which is built to withstand the demands of school libraries. But hey, that means it'll withstand all those re-readings you're sure to give it! Hopefully the binding will ensure that used copies are still in good condition too.

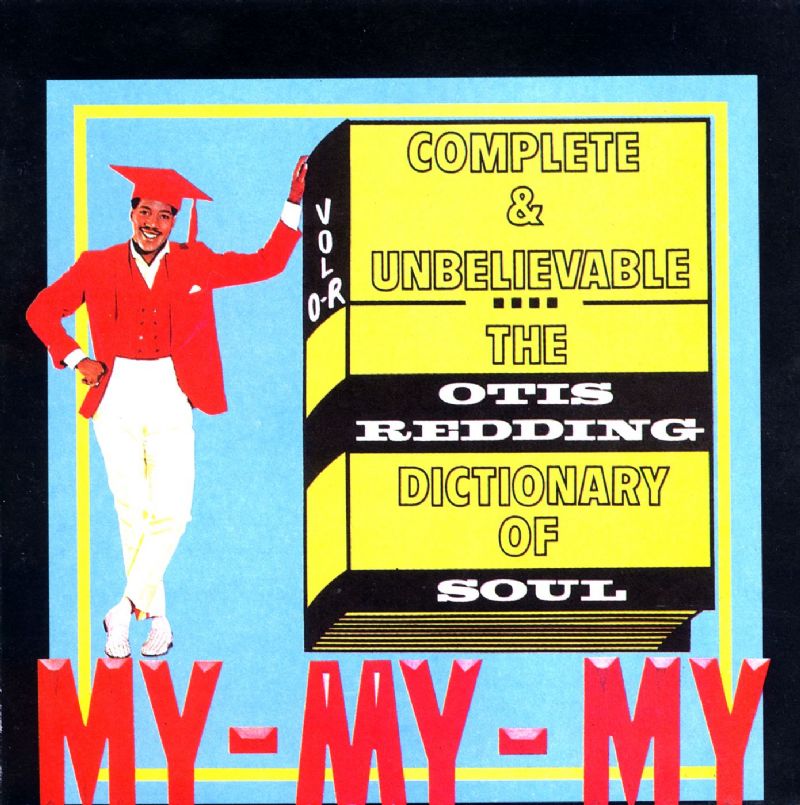

American R&B starts with R.C. Robinson messing around on piano at a shop in Greenville, Florida. R.C. later became Ray Charles, who helped distill black America's disparate musical expressions--the blues, gospel and jazz--into an explosive new genre. Rhythm and blues.

Artists like Charles, James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Janet Jackson and Teddy Riley are towering, influential figures in the genre's history, and get their due in the book. I also tried to emphasize the regional scenes and labels that have left their mark, from teens singing doo wop on New York street corners, to Motown's musical assembly line in Detroit. Cities like Memphis, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Minneapolis revolutionized how R&B was created, what it was about, and how it sounded. Readers in those cities will get a bit of local history with their soul.

R&B also existed within historical and social contexts. Readers learn about how racism and segregation shaped the genre from its earliest expressions, and hopefully come away with an understanding of how R&B fits into the broader contours of black history.

Mostly, though, American R&B is about incredible music. Writing this book was a great experience, but sometimes a frustrating one. That was never the case with putting on Isaac Hayes, the Ronettes, or Off The Wall. It's been exciting seeing our culture get excited about R&B again, whether it's Adele or Frank Ocean. And the genre is shifting in really fascinating ways right now (if I had to guess, this might hold a clue to where we're headed). R&B has such a rich and varied history--you could spend the next year obsessed with classic Motown, 80's funk, disco divas, or obscure soul compilations, and literally hear nothing but passionate, beautiful music. There are a handful of playlists and an appendix of must-haves in the book. They scratch the surface.

That's what the book does too. It's a survey, and at 64 pages, a pretty quick read. There are certainly omissions. (sorry, Gladys Knight and Rick James!) But the goal was to write a concise, engaging review of a complex and evolving art form. If any educators out there have questions about the book, you're welcome to get in touch via email.

I hope you'll read American R&B: Gospel Grooves, Funky Drummers & Soul Power. I'm proud of it. But it's no substitute for the primary sources:

Wednesday, August 8, 2012

American Hip-Hop: Rappers, DJs and Hard Beats (Out Now)

As I keep saying, very exciting times here at Rockaliser. For one thing, I wrote a book:

by Nathan Sacks

Available at Most Online Bookstores Within the Greater Googlesphere

It's a textbook about rap music, covering the history of the genre from its origins in the South Bronx to the present day, written with a middle school/early teen audience in mind. This entry represents one of six genres featured in Lerner Publishing's "American Music Milestones" series--the others are rock music, Latin music, country, pop, and soul/R&B, the last of which you will be hearing more about soon. Check out all the titles on Amazon.

While American Hip-Hop: Rappers, DJs and Hard Beats is written for younger readers, it can be read by curious music fans of any age. My hope was that kids and hip-hop laymen alike would be able to pick up this book and learn a decent amount of history in sixty scant pages. The book covers a lot of ground, and is full of neat sidebars and extras, like "Must Download" playlists, timelines, and glossaries of terms, all of which are calibrated for maximum new listener pleasure. If there's one thing that bothers me about the finished product, it's that I had to leave out a lot of artists because of word constraints (a partial list of really, really important rappers I couldn't get to: Busta Rhymes, Kool Keith, Das EFX, Gang Starr, EPMD, Redman, the Beatnuts, E-40, T.I., the Fu-Schnickens, MF Doom--the more I rattle off the worse I feel). Nevertheless, despite its manifold, unforgivable errors of omission I do think the book effectively condenses forty years of music, politics, controversy and fashion in a digestible and entertaining package.

I've always wanted to write a book, and as far as introductory-level work-for-hire gigs go, this was the jackpot. Even when I struggled at certain points--say, when forced to cut entire sections about Fear of a Black Planet--I could rely on the input and patience of editors far more experienced than me, who knew and supported exactly what I was going for but nevertheless tamped down my enthusiasm for random, irrelevant historical trivia. Freelance book-writing gigs, especially for younger, inexperienced writers, can be nightmarish and painful, but this one was almost disturbingly pleasant.

More importantly, working on this book broadened my appreciation for the genre, which was already substantial. I listened to hundreds of albums, studied rap style and wordplay, researched samples, and read every book I could get on the subject, aiming to get the most complete picture of rap music in my head that I could. The best consequence of this was an enhanced understanding of the hip-hop's capacity for social change, built into the genre from the very beginning. To understand hip-hop, it is important to picture the impoverished and segregated Bronx of the 1970s, a bleak period for the borough which nevertheless inspired these amazing innovations in sound first introduced by DJ Kool Herc in 1973.

Rap music is not a politically neutral art form. It is only recently, after all, that journalistic "neutrality" in the public sphere has come to be seen as a virtue, and this notion is complete nonsense. Hip-hop is about the individual voice as an instrument of radical change. Forget the boring arguments about what is and isn't "authentic" or "real" hip-hop. A rap scene that doesn't challenge prevailing notions of authority and privilege, that wastes its resources on celebrity gossip and beefs and other such nonsense, is denying its own radical history. That's a plain and obvious fact. In writing about some of the controversies that have fueled misunderstandings of hip-hop culture, I touch on some characteristics of modern race relations that are rarely articulated in the public school classroom. I strongly believe hip-hop remains a relevant mode of expression because it is uniquely capable of contextualizing sometimes dark themes in a profound, uplifting and exciting manner. For younger audiences, hip-hop is an especially potent method of expressing complex ideas about race, politics, and class.

It's a really great time to be a hip-hop fan in 2012. There have been reams of amazing albums to come out this year. Off the top of my head, I can think of killer LPs or mixtapes from Curren$y, Masta Ace, DJ Premier and Bumpy Knuckles, Killer Mike, El-P, Big K.R.I.T., Devin the Dude, The Alchemist, Large Professor, Odd Future, Ab-Soul, and probably others. Rick Ross' new album is shockingly brilliant, as was his mixtape Rich Forever from earlier this year. And the year is only half over, with more to come from beloved veterans Ghostface Killah and Big Boi as well as young upstarts Kendrick Lamar and A$AP Rocky. Hip-hop is entering a remarkable new era, with new scenes incubating every day in less densely populated regions of the country. Even my home state of Iowa seems poised for a decent, breakout rapper to make it big in the next few years. Despite the think pieces proclaiming "hip-hop is dead" every few years, the amount of amazing rap music seems to be growing exponentially, as more rappers choose to circumvent the major label system and release music directly on the Internet.

Anyway, all this rambling may be a bad way of trying to convince you to buy my book (if $30 seems excessive--which I totally understand--there are an array of cheaper prices at non-Amazon bookstores). American Hip-Hop is ideal for kids interested in exploring the genre, and already it's garnered a couple of positive reviews from adults as well. Teachers might especially be interested in using it as a potential classroom resource--anyone is invited to email me here with questions or suggestions about using hip-hop in an educational setting. If you like what we do at Rockaliser, please check out this book: it might not be the most comprehensive ever written on the subject, but it conveys what it knows with what I hope is real, palpable enthusiasm for the music and the culture, both of which I have come to respect more than ever.

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

The Rockaliser 30: 30 Days Later

All month long at this blog, we have brought you the Rockaliser 30, a daily series devoted to classic albums that have been eclipsed, forgotten, misheard, or otherwise not given their propers. We began with Hawkwind and ended with Vanity 6, devoting space in between to everyone from Edan to Ike Turner, Solomon Burke to Rod Stewart. Our hope is that you found this series of two-and-a-half dozen essays edifying, enough at least to check out some of the albums in question. Above, we've compiled a 30-track playlist featuring every song spotlighted over the course of July. And here is the master list:

Day 3: Delinquent Habits (1996)

Day 5: Felt (1971)

Day 8: Caetano Veloso, A Little More Blue (1971)*

Day 12: Bedhead, WhatFunLifeWas (1994)

Day 13: Manzel, Midnight Theme (2004)

Day 14: Rick James, Street Songs (1981)

Day 16: 801 Live (1976)

Day 18: Marvin Gaye, I Want You (1976)

Day 20: Edan, Beauty and the Beat (2005)

Day 27: Tank, Power of the Hunter (1982)*

Day 30: Vanity 6 (1982)*

Most of these albums are to available to listen to for free on Spotify--those that are not, you will see I have placed an asterisk by.

If you were reading, thanks for reading. If not, all the pertinent links are above. Don't forget to hit us on Twitter, etc., as a wise man once said. And we certainly aren't done here yet. More news to come in the next few days, of "bookly" proportions.

Now if you'll excuse me, I'm due to re-enter the world of Bill Wyman's dreams:

Monday, July 30, 2012

The Rockaliser 30: Vanity 6 (1982)

[Welcome To the Rockaliser 30, a month-long series devoted to classic albums that have been eclipsed, forgotten, misheard, or otherwise not given their propers. This is Day Thirty. Archive here.]

As was the case with so many records emanating from Minneapolis in the early 80’s, the record sleeve for Vanity 6’s debut doesn’t tell the full story. Scanning the back cover, we learn the group is made up of Brenda, Susan, and Vanity, a tough-looking, interracial trio who favor lingerie. We see the racy song titles, including the opening salvo of “Nasty Girl,” “Wet Dream,” and “Drive Me Wild.” And there, at the bottom, it says “Players: The Time; Produced and Arranged by the Starr Company and Vanity 6.”So there you have it--Vanity 6 features the instrumentation of The Time and the production of Jamie Starr. Which means that Prince wrote, produced and arranged the entire thing, with zero input from either The Time or Vanity 6.

As with The Time’s debut, this album is a struggle for Vanity 6 to carve out their own identity, while singing Prince’s words over Prince’s music. The quality of the songwriting makes that tough. First single “Nasty Girl” features the slipperiest beat Prince ever threw together. Like “Sign ‘O’ The Times,” the sound might have been too futuristic for its own good. The song was a dancefloor hit, but didn’t make the Hot 100. Twenty years later, Timbaland was constructing beats that sound remarkably like “Nasty Girl,” and they still sounded futuristic. It’s a classic, with a vocal from Vanity that writhes and preens as much as the funk guitar that adorns the song.

Elsewhere, Vanity 6 tends towards the new-wavey funk that Prince explored in the early 80’s. “Wet Dream” is a companion to 1999’s “Delirious,” and “He’s So Dull” wouldn’t have sounded out of place on a Blondie album.

Those tracks all feature lead vocals from Vanity, the most distinctive of Vanity 6’s singers. On their lead vocals, Brenda and Susan sound more anonymous, overshadowed by the crisp pop-soul, with the ubiquitous synthesizers and LinnDrums of the Minneapolis Sound.

Predictably, the album’s best vocal comes from Prince himself. “If A Girl Answers (Don’t Hang Up)” is framed as a phone conversation between women arguing over a man. Over a bouncy funk bass, Brenda and Vanity call Jimmy, only to discover a woman on the other line. They verbally assault the lady, Vanity sounding a bit stiff, Brenda reeling off some serious insults. But the woman on the other side of the line--that’s Prince as Jimmy’s girl--is a high-pitched, sharp-tongued force of nature. Jimmy’s Girl is basically rapping, with an impressively loose and angry flow.

Vanity 6 is rounded out by a couple songs that sound a bit like “Computer Blue,” and a sappy finale. It was the only album this group would release, as group members chafed under Prince’s control freak tendencies. Today, Vanity 6 is a mostly forgotten Minneapolis Sound footnote, and that’s a shame. These three nasty girls--gleeful and matter-of-fact in their forwardness--and the prolific genius manipulating things behind the scene had it going on.

Sunday, July 29, 2012

The Rockaliser 30: The Roy Ayers Ubiquity, Vibrations (1976)

[Welcome To the Rockaliser 30, a month-long series devoted to classic albums that have been eclipsed, forgotten, misheard, or otherwise not given their propers. This is Day Twenty Nine. Archive here.]

With its smooth-buttered soul arrangements, cracking backbeats and hazy wisps of psychedelia, Roy Ayers' Vibrations was an album destined to be rejected by jazz purists. And yet the vibraphonist didn't necessarily intend the album as an overture to his soul/funk/acid jazz fanbase, either. Like fellow crossover fusion artists Herbie Hancock, Donald Byrd, and Brother Jack McDuff, Ayers saw an appealing midway point between vocal funk and jazz, especially as the former came to prominence in the early 1970s. Songs like "Domelo (Give It To Me)" and "Come Out And Play" were first and foremost ripping funk rhythms with dips into jazz tonality and instrumentation. Other songs, such as "Better Days" and "The Memory," set a smooth template for what would become quiet storm funk. Vibrations nominally belongs in the category of "jazz fusion," but even as fusion goes it has a lot more in common with Isaac Hayes than, say, the Weather Report.

On those rare occasions when someone asks me for a decent introduction to acid jazz or jazz fusion, I tell them to put on the first side of Vibrations, forget the convenient genre descriptors, resist the temptation to mock, and just let the sound envelop you. Ayers is no vocalist--I was once at a party where I tried to play "The Memory," and it provoked very little reaction, apart from comments that the vocals "weren't that great" (granted, we had just been listening to Otis Blue, but that's an outrageous standard when comparing vocal prowess). Even his vibraphone performances are confined to small moments, like the tinkling in the background of "Searching" (later sampled by Pete Rock & CL Smooth) and the title track. But where the jazz lacks, the layers of pop arrangements seem brighter. Vibrations' final number, "Baby You Give Me a Feeling" is a monstrously effective pop song, romantic and dizzying, repetitive and yet never wearying. And the beat is imperishable. When Ayers and his band start chanting "feels so good, feels so good" like a stuck emotional record, it is hard not to jump out of one's seat and jam along.

Will I live to see a Roy Ayers resurgence? Will his albums on Polydor ever be released and remastered, with lovingly detailed liner notes and bonus tracks? Hip-hop used to be the one scene that paid fusion artists any mind at all, and yet nowadays that part of the genre's institutional memory seems to have been lost. Recently, I was listening to Frank Ocean's new album, which is being hailed as a sea change for R&B. But that album does have its moments of spare electronic formlessness, and sometimes I felt myself thinking--this part seems empty, could use a vibraphone solo. That's not a rational critical response, but if the purists were more forgiving about Vibrations back in 1976, maybe my line of thinking wouldn't seem so odd today.

Although it probably would.

With its smooth-buttered soul arrangements, cracking backbeats and hazy wisps of psychedelia, Roy Ayers' Vibrations was an album destined to be rejected by jazz purists. And yet the vibraphonist didn't necessarily intend the album as an overture to his soul/funk/acid jazz fanbase, either. Like fellow crossover fusion artists Herbie Hancock, Donald Byrd, and Brother Jack McDuff, Ayers saw an appealing midway point between vocal funk and jazz, especially as the former came to prominence in the early 1970s. Songs like "Domelo (Give It To Me)" and "Come Out And Play" were first and foremost ripping funk rhythms with dips into jazz tonality and instrumentation. Other songs, such as "Better Days" and "The Memory," set a smooth template for what would become quiet storm funk. Vibrations nominally belongs in the category of "jazz fusion," but even as fusion goes it has a lot more in common with Isaac Hayes than, say, the Weather Report.

On those rare occasions when someone asks me for a decent introduction to acid jazz or jazz fusion, I tell them to put on the first side of Vibrations, forget the convenient genre descriptors, resist the temptation to mock, and just let the sound envelop you. Ayers is no vocalist--I was once at a party where I tried to play "The Memory," and it provoked very little reaction, apart from comments that the vocals "weren't that great" (granted, we had just been listening to Otis Blue, but that's an outrageous standard when comparing vocal prowess). Even his vibraphone performances are confined to small moments, like the tinkling in the background of "Searching" (later sampled by Pete Rock & CL Smooth) and the title track. But where the jazz lacks, the layers of pop arrangements seem brighter. Vibrations' final number, "Baby You Give Me a Feeling" is a monstrously effective pop song, romantic and dizzying, repetitive and yet never wearying. And the beat is imperishable. When Ayers and his band start chanting "feels so good, feels so good" like a stuck emotional record, it is hard not to jump out of one's seat and jam along.