Available on DVD

You are reading Stones on Film, a 13-part dialogue covering notable Rolling Stones documentary and concert films through a critical lens. Today is week four. Archive here.

NS: I had a chance to walk through Hyde Park a number of times while staying with my father in London a couple years ago. Our hotel was by the north entrance near the Lancaster Gate tube stop, so I was able to spend several afternoons walking along the Serpentine, visiting the memorials, and imagining what it would have been like to be at the Rolling Stones’ famous 1969 festival.

The event recorded in Stones in the Park is one of the most famous concerts, and arguably one of the most famous pop culture moments, in British history. Certainly it is one of very few pop concerts that a rock layman might be aware of. It has been referenced in pop culture often since--for instance, in an issue of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Alan Moore portrayed a fictional version of the Hyde Park events with Mick Jagger’s character from Performance, Turner, presiding in place of Mick. The Stones set the standard for the legendary rock concerts that Hyde Park would become famous for. The event was also notable for being massive and free. As the film shows, there are definite disadvantages to throwing free shows in huge parks (to say nothing of adverse effects on the environment). Tellingly, the Stones charged customers a great deal for an anniversary show last year.

The film Stones in the Park finds the band at a dispiriting crossroads, performing for the first time in months with a new guitarist, the Bluesbreakers’ Mick Taylor, only two days after Brian Jones drowned to death. Taylor had been hired before Jones passed, but was suddenly thrust into the position as the permanent replacement of a dead Stone. He looks shy and uncomfortable here, but his guitar-playing is anything but.

It is a known truism among hardcore Stones fans that Mick Taylor was the best musician to ever play with the group. The funny thing about Stones in the Park is how immediately this becomes apparent--Taylor, even in glimpses, is a musician and talent unlike anything in the Stones at the time. His addition and Jones’ subtraction from the band changed so much about the group’s sound. Whereas Jones’ guitar was barely audible in Rock and Roll Circus and Sympathy for the Devil, Taylor’s crystalline leads are not only present, but equal in the mix with Keith Richards’ meaty rhythms. It is a bit sad that at this supposed memorial of Brian Jones, his replacement so quickly proved to be an improvement over his predecessor. Even in the one area of guitar-playing where Jones showed promise--slide guitar--Taylor outplays him with a quick-fingered grace and mournful beauty that is equalled by very few, the difference between a virtuoso and a mere player.

Taylor’s addition to the group propelled its sound several degrees forward, but it wasn’t the only new element. The Hyde Park concert was also the first public opportunity for Keith Richards to test out his new open tuning style, which he picked up from Ry Cooder. That switch from standard tuning to open-G permanently warped Keith’s playing, Keith and Mick’s songwriting, and the band’s performance style. With this new tuning, Keith could throw away the standard barre chords and lead lines and hang back behind Charlie’s drums and play chunky rhythms and mangled three-string clusters (“Five strings, three fingers and one asshole” he famously said).

It’s hard to describe why, but these new developments increased the sophistication of the sound by several factors. Consider the differences between the version of “Satisfaction” in Charlie is my Darling and the version here. In the earlier version, the main riff is a low, reedy, two note thing. Here, the riff is exploded outward. Keith plays higher on the fretboard, bending entire chords rather than single note lines. The result is a pure choppy rhythmic momentum completely undivested from the traditional rock lead guitar trap he seemed to be falling into (see: his passive noodlings in Sympathy for the Devil).

The unfortunate thing about Stones in the Park, however, is that the pieces are all there for potential greatness, but the band was either too fazed by Brian’s death or completely unprepared to play live after many months apart. Simply put, they blew it. It is astonishing how often at Hyde Park that the Stones fuck up their set. The band basically loses the road map for several measures in “I’m Yours, She’s Mine,” and Bill Wyman audibly fucks up several times during “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” (c’mon Bill--you wrote the riff!). The band is simply not together here, in a way that is much more apparent even than Rock and Roll Circus.

Even more odd is how disengaged Mick Jagger seems, onstage and off. To again compare this to Charlie Is My Darling--remember the interviews where Mick talked about how “pop music is an ephemeral thing”? He was a bit pompous and his wisdom was conventional, but he was at least being earnest and thoughtful. In Stones in the Park, Mick spends his interview sections either complaining about the expenses of being a rock star, or grousing about and insulting the intelligence of his audience.

To be fair, he has a point about this audience--Stones in the Park also features Hell’s Angels as security, driving trucks through lines of people and dragging people offstage like some sort of pre-punk rally. One of the odder preoccupations of directors Leslie Woodhead and Jo Durden-Smith is a focus on the most annoying, unpleasant elements of the audience. They provide interview clips from obnoxious socialists, meathead macho rockers who disparage the Beatles, eccentric Britishers, and people just trying to bring back the swastika (hey, it used to be a symbol of love!). This makes parts of the film seem like a prequel to the tenor of barbarism and death that many associate with the Altamont concert and Gimme Shelter.

I’ve talked a lot about how the performances are disappointing, but even the Stones at their messiest and most unfocused will yield some good moments, and this is the beginning of their greatest period. The same cannot be said for the filmmaking here--Stones in the Park is truly badly filmed and badly edited. For some reason, Woodhead and Durden-Smith love fast zooms that go in and out, almost as much as they like quick cuts, leading to visual whiplash that is annoying and distracting. They do a terrible job focusing on the band. Even Keith is barely visible on stage most of the time. Woodhead and Durden-Smith clearly are trying to keep the cutting and pacing fast to match the energy of the music, but the ultimate effect is so amateurish, I found myself bored and even a bit nauseated by the number of quick zooms at the backs of people’s heads. There were a number of concert films from this era that employed this nauseating zoom-and-cut style, such as Cream’s farewell concert.

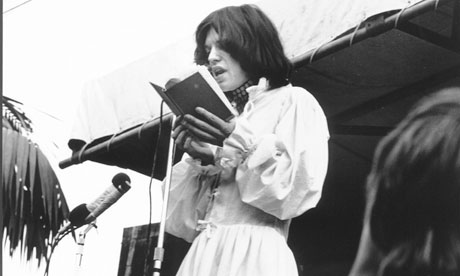

What did you think of the tribute to Brian? I had heard so much about the poem, Mick’s dress, and the butterflies, but there is little here that actually celebrates Brian or his legacy. Some Brian fans have maintained that the choice of “I’m Yours, She’s Mine” was Keith’s slap in the face to the deceased Stone whose girlfriend he had stolen. I don’t know about that, but I almost couldn’t believe myself listening to Mick’s reading of Shelley’s Adonais, which was all about how much harder it is for the living to continue on, and the dead have it lucky (there’s a reason Mick loved his romantic poets so much). Were the Stones even processing that Brian was dead at this point? Who among them, do you think, was even capable of caring?

AM: When your band’s founding member dies two days before you play an enormous, free concert in your hometown, you have a few options: pay tribute, cancel your show, or ignore it entirely. Unfortunately, the Stones make paying tribute seem like the worst option of the three. How convenient that Brian was simply “awakened from the dreams of life,” as Shelley put it. Seriously, how callous does Jagger have to be to say “I don’t believe in Western bereavement” two days after Jones’ death?

The band’s (which is to say Jagger’s) response to Brian’s death is incomprehensible, and uncomprehending. Jagger is far more lucid when discussing the profitability of early Rolling Stones concert--the cold business logic comes to him far more naturally than empathy.

Then again, nobody ever said this band was great because the people in it were humanitarians.

Much to discuss here, especially given the brief runtime. I enjoy the Stones’ performance more than you do, I think, to me it’s a clear cut above Rock and Roll Circus. You analyze why the addition of Taylor and the transformation in Richards’ riffing altered the band dynamic, and do it far better than I could, so let me just second what you say.

But there’s several jaw-dropping moments here, mostly courtesy of the newest Stone (now vying with Wyman for title of “most stone-faced Stone”). His dirty slide is a revelation throughout. I think it’s important to recall that here, as it was 6 months ago with Rock and Roll Circus, the Stones are not a touring band. So, sure, they’re a bit sloppy. But I enjoy almost everything they do.

Whatever Keef’s motivations, it’s lovely to hear the band roar to life with “I’m Yours & I’m Hers.” The slow churn of “I’m Free” sounds like a Sticky Fingers cut. There’s a boisterous, barbed “Satisfaction.” And a scrappy “Honky Tonky Women” is rough, and kind of drags its feet, but in a way that anticipates Exile (the muddled mix here does no one any favors, especially Wyman’s bass).

While this version of “Sympathy” has a bit of fat there are some astounding moments. The way Richard’s Flying V rises up from that unholy drum circle! The way that Taylor’s terse rhythm guitar flies around in circles with those same drums! And the way that the film’s editing actually serves the song! It’s great stuff.

I choose “Love In Vain” as the show’s weakest moment. It’s a song almost too lonely to expose to a crowd of hundreds of thousands--Robert Johnson didn’t conjure his songs for that.

Let me get to the villains of Stones In The Park: Leslie Woodhead and Jo Durden-Smith, the directors. The movie is a confused mess, inelegantly blending together elements of the concert film, cinema verite, and stodgy BBC documentaries. The directors never fit together their puzzle pieces, they just kind of leave them all on the board and dress them up with weird editing decisions (like those whiplash-inducing zooms).

The movie starts with a montage of sleeping faces, goes to the Stones halfway through “Midnight Rambler,” shifts to a dry voiceover providing background information on the concert, shows a seated Jagger musing on crowd psychology, then provides a montage of freakish looking Angels striving to redeem the Swastika. That’s all in the first seven minutes.

This is a film that cannot decide what it wants to be. Is it a documentary that takes us through this day at Hyde Park? Or a tour diary, following the Stones around? Perhaps an avant-garde concert film? Durden-Smith and Woodhead have no clue.

I had some harsh things to say about Godard’s direction, but this movie had me pining for the clarity of his artistic choices. Ah, to watch a film about the Stones that is coherently structured, thoughtfully shot and well-edited (The problems with Sympathy mostly revolved around its content). Durden-Smith and Woodhead evince no such thoughtfulness, and appear to be some of the least probing interviewers to have ever sat down with Mick Jagger. The film only gains momentum when they allow the Stones to play, unencumbered by trips to King’s Road or the inside of Jagger’s car.

I’ll wrap up with a more general Stones question: just how central is “Sympathy for the Devil” to the band’s legacy and image? The last three Stones films we’ve watched all feature “Sympathy” as their musical showpiece. The band exults in letting loose its percussive onslaught and gleeful darkness. They seem to see it as the crown jewel in their catalog.

Is that because it really is? Or is it a simply a quirk of these three movies all being filmed as “Sympathy” was being recorded and promoted (Let It Bleed was not yet out when Stones In The Park was released)? I love “Sympathy,” but there’s a half-dozen songs from this period that are at least as good, to my mind. From a historical standpoint, “Jumping Jack Flash,” which saw them casting off the psychedelic frills, was more significant. Why this song, again and again?

NS: There’s actually one bit in the film that shows Mick’s basic humanity, a scene in a car with Marianne Faithfull and her son Nicholas. Mick and the boy have a conversation about “waving to Charlie” and whether or not the drummer will wave back. Mick for once is generous and friendly, and the moment seems real and unrehearsed. However, this also demonstrates another trend I have noticed in Stones docs, the reduction of Faithfull to the status of non-entity. It’s worth thinking about how much she was vilified in the British tabloids for being both a mother and involved with Mick. Male rock stars like Jagger and Richards were rarely savaged in the press for being drug addicts or neglecting their children, but a different standard was applied to females like Faithfull. This is all tangential to the movie we are watching, but worth remembering when seeing how she interacts with Mick and her young son.

Why is “Sympathy” such a popular live choice, you ask? You mention “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” as a more significant and perhaps recognizable song in the Stones canon. Why don’t they play that song as often? For that matter, why have we not yet heard a single live version of “Street Fighting Man,” another song that is musically and socially significant?

My guess is that it has something to do with “Sympathy”’s musical and lyrical flexibility. Think about it: the song’s relatively simple three-chord structure and extended jam sections are tailor-made for a variety of different interpretations, especially with regard to the rhythm (although the version played here with percussionists is more similar to the studio version than most). On top of that, the lyrics of “Sympathy” are vaguely dark and foreboding, but not explicitly about anything current, making them perfect for summoning societal or generational angst without dating themselves (note when he says “I shouted out who killed all the Kennedys”--he is talking persistent historical trends, not any one event). The mantle of “dark, foreboding Stones song that represents the sins of hippie culture” largely went to “Gimme Shelter” after this, largely because of the movie, but it’s still easy to see why the Stones would bring out “Sympathy for the Devil” as their set piece. It grooves, it terrifies, and it moves the listener along through a compelling narrative that can be universally understood in almost any culture.

We certainly do differ regarding the general level of quality of the Stones’ performance, which I see as riddled with mistakes. Part of that could be the low quality of the recording here. Certainly there are many good musical moments, many of which you describe, and my favorite overall is probably the opening performance of “Midnight Rambler.” Simply the part where Taylor and Richards are playing together, bouncing the song’s main riff back and forth, as footage plays of people entering the park. The synergy between their two guitar styles is extraordinary--there really is nothing like it--and it definitely shows the band was on to a special sound. And the extended performance of “Sympathy” is also fun. However, other songs are badly out of tune, and the band at times seems genuinely confused at what is happening within a song. Even normally superwound Charlie seems to make mistakes.

Glad to see we agree about Durden-Smith and Woodhead, two BBC documentarians who between them have a number of rock films to their credit. Why, then, is this one so amateurish? Even at an hour, the film seems long, full of extended boring moments that drag forever, many involving Jagger or members of the audience.

One thing that Durden-Smith and Woodhead might have done to improve the film (other than hire another editor) is intersperse footage from some of the openers. The Stones were clearly leery of shining a spotlight on opening acts after being bested by the Who, meaning we never see or hear a mention of groups like King Crimson, Roy Harper, and Alexis Corner’s New Church. Crimson supposedly put on a legendary show at Hyde Park, and three of their live performances became instrumentals for In the Court of the Crimson King. Imagine if there had been footage of Jagger with Robert Fripp and co., introducing throngs of a fans to “a new band that is gonna go a long way”--It would have been interesting historically, at least.

Before we leave Hyde Park behind, what did you think of last year’s 44th anniversary (?) Stones Hyde Park shows, with Mick Taylor in tow? Did the addition of Taylor on “Midnight Rambler” at recent Stones gigs make you any more interested in seeing 2013 Stones live? I have to admit I’m interested in seeing Taylor play, but promise I draw the line at hologram Brian Jones, or cardboard cutout Ian Stewart, or Bill Wyman’s son Wolfgang on bass, or, or...

AM: I agree--cut the interviews with dazed hippies and politically confused Angels, and give us more “Midnight Rambler.” One of the most villainous songs the Stones ever did, and starting the film with its slow crawl seems like a smart directorial move. But even there the filmmakers fuck up--Keith has called it a “blues opera,” but Durden-Smith and Woodhead chop off the first few acts. For shame! (I can’t write about this performance without linking to the astounding version that they’d perform later in 1969, captured on Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out.)

Thanks for bringing up the scene in the car with Mick, Marianne and Nicolas. There was a lot of shit going on for all three of them outside that car, but they manage to share one sweet moment while they ride to the hotel. Little Nicolas isn’t Jagger’s son, but you can see him bring out a fatherly impulse in Jagger. He melts Jagger’s often-remarked-upon coldness a bit, and I love the detail that Charlie is his favorite Stone. Good taste!

As for the Stones concert at Hyde Park again in 2013...it was hard to care, wasn’t it? I didn’t check, but I don’t imagine the front pages of the (remnants of the) British music press read “Stones Reassert Artistic Credibility at Stunning, 4-Hour Hyde Park Show.”

Almost no one seems excited by the Stones’ current tour, and that includes the guys in the band. Charlie Watts hates playing outdoors, Mick Taylor has moaned about the briefness of his cameos, and Jagger publically questioned Richards’ and Taylor’s fitness to perform. (Jagger also revealed to Q that he shares Ian Rubbish’s political views.) Sales for the tour have been soft.

The Rolling Stones are probably my favorite band, and yet I didn’t even consider going to see them when they passed through Oakland last May. Instead, I saw Yo La Tengo that week, a band whose work ethic and modesty are the polar opposite of what the Stones represent (though they do a decent “Let’s Spend The Night Together”).

A lot has changed for the Stones since 1969, when 250,000 people went to see them flub a few notes and tear into some classics, free of charge. In Stones In The Park, Jagger says “it never occurred to me why people should really pay. You know you don’t make any money.” By 2013, he’d changed his mind--it cost more than $200 to witness the Stones retake the stage at Hyde Park.

No comments:

Post a Comment